The First Colorado Cycling Summit

Cycling Season is here, and so is a long list of epic rides throughout the state and surrounding states. Are you ready? Join Avid Cyclist, and other co-hosts for the

The 3,000 gravel riders who do SBT GRVL each summer love how the route takes them through bucolic ranchland. Ranchers want them out. The race’s future is under scrutiny.

Discussion reached an aggravated pitch when 70 or so ranchers crowded the Routt County commissioners’ hearing room in October to air their grievances about a gravel bike race that had come through their corner of the county a few weeks before and left most of them seriously rattled.

Gravel riding is a niche of cycling involving long distances on gravel roads, on what look like road bikes but with fatter, knobby tires and a slightly cushier frame. It exploded in Colorado in recent years when cyclists, looking for an alternative to road riding, took to the dirt and gravel roads ribboning across the state through bucolic landscapes and breathtaking beauty. A diehard community of enthusiasts quickly emerged, which started organizing gravel-specific races and events.

The Steamboat Springs race, dubbed SBT GRVL, started in 2019 with 1,500 riders and quickly grew to 2,500 riders. By 2022, a lottery capped entries at 3,000, where it remains. It is one of the largest gravel bike races in the world, with four courses ranging in length from 37 to 142 miles that start in Steamboat, loop through the Yampa Valley and wind along county roads through Routt County ranching communities.

The number of riders and the location are at the heart of the conflict between SBT GRVL and the Routt County ranchers. That type of conflict is growing in rural communities across Colorado as outsiders flock to a place because of its beauty and recreational value, but in doing so, some say, upset a community’s heritage and threaten its values.

SBT GRVL riders, promoters and those who champion the event for its inclusivity say they should be allowed to ride through Routt County because of the money they pump into the local economy each fall. But the ranchers say the riders’ trash, selfish attitudes and disregard for safety are more than they can take, and that they don’t see any benefits from their spending. Now five years into reckoning with a four-day event in August that annually disrupts their busiest agricultural season, they want the commissioners to do away with it. The race’s future now hinges on commissioners’ review of their permitting process

Depending on what the commissioners decide, the race could end or find itself hobbled by new regulations, just as the Colorado Tourism Office and the Outdoor Recreation Industry Office are pushing gravel biking as Colorado’s next big thing and pumping money into events, promotion and how-to guides everywhere from Fruita to Ridgway to Pueblo to Elbert and Moffat counties.

Conor Hall, director of the Outdoor Recreation Industry Office, says his team is excited to work with communities in recreation hot spots like Steamboat Springs “to champion their visions and provide resources that can bolster their recreation economies.” But he also recognizes the importance of balancing growth with a community’s heritage and natural resources. The question is, can growth and preservation exist? And can Routt County’s growing pains inform other communities potentially destined for the same?

One by one at the commissioners’ meeting on Oct. 16, the ranchers expressed their frustration.

Among their top complaints were the throngs of riders who started pushing into the county days before the main event. Then there were the spectators, they said, who ballooned the riders’ number, parked their cars willy nilly and added to the general disruption on the roads ranchers use daily to transport their cattle, hay and 4-H kids. The spectators were almost as annoying as the cyclists, with their cowbells that clanged incessantly, some ranchers said. But the fact remained that the riders also pumped millions of dollars into the local economy through lodging, dining and shopping during the event week.

Nearly all of the registered riders stayed, ate and partied in Steamboat Springs. But when they took to their bikes, they bled onto a series of county roads that passed dozens of ranches many say are just as — or more — responsible for putting Steamboat on the map as its world-class fly-fishing or trademark Champagne powder.

Steamboat’s ranching heritage had certainly been there longer than the new gravel-riding phenomenon. Sure, Routt County’s agricultural economy is just a fraction of the size of the region’s ski-anchored recreation industry. But the ranchers said they were the heart and soul of the place and that they would never have invited this much mayhem into their lives, no matter what kind of benefits SBT GRVL, the chamber of commerce or the Colorado Tourism Office claimed outdoor recreation brought in.

The race fell on the final weekend of the Routt County Fair, which many ranchers call their most important event of the year, and during the final days of haying season, when they are racing the weather, daylight, equipment breakdowns and other obstacles to get their hay cut and stacked in time to cure.

At the race start in downtown Steamboat Springs, the riders lined up according to the course they were going to ride. First went the serious racers, chasing prize money, on the black course 142 miles long. Then came the red and green course riders pedaling 37 and 60 miles. The blue course riders went last, grinding out 100 miles. They all rode toward a series of county roads that made a giant loop heading south and then north of Steamboat. But the frontrunners were so fast that by the time they had hit the northernmost apex and were on their return via a stretch of road that doubled back on itself, they ran into thousands of riders going out, creating two-way traffic.

The confluence of events created instances like the one Christy Belton said she had when a wall of racers approaching her truck as she was creeping along started yelling at her “upset because I had the nerve to be on the road.”

Chuck Vale, a rancher retired from a 49- year career in the county’s emergency services system, said an ambulance trying to reach a rider who’d crashed on the course couldn’t because “the race people stopped it from cruising down the road to arrive at the event.” Jo Sanko, who’s been ranching the area for decades, saw a “sports garment” lying in her driveway and lifted it with a stick because the owner “had used it to wipe themselves.” And cows Trenia Sanford cares for broke through a fence “when they saw a 26-headed animal racing down the road,” she said. Her hired hand helped corral them. “But you’ve seen cows run. You know they can buck and twist and move sideways. These bikers had no idea what kind of danger they were in,” she told the commissioners.

year career in the county’s emergency services system, said an ambulance trying to reach a rider who’d crashed on the course couldn’t because “the race people stopped it from cruising down the road to arrive at the event.” Jo Sanko, who’s been ranching the area for decades, saw a “sports garment” lying in her driveway and lifted it with a stick because the owner “had used it to wipe themselves.” And cows Trenia Sanford cares for broke through a fence “when they saw a 26-headed animal racing down the road,” she said. Her hired hand helped corral them. “But you’ve seen cows run. You know they can buck and twist and move sideways. These bikers had no idea what kind of danger they were in,” she told the commissioners.

The race was a danger to more than people’s bodies, the ranchers insisted. They called it an affront to Routt County’s agrarian values, “unsafe for its citizens and producers” and “one of the worst examples of nonrepresentational government” they’d ever witnessed.

The public outcry at the Oct. 16 meeting was sustained enough that the commissioners decided to do a full review of the special use permit that allows SBT GRVL and 16 other highly popular events, including the Emerald Mountain Epic mountain bike and running race and the Steamboat Marathon/Half Marathon/10K, to operate within Routt County.

At issue was the fact that Routt County’s special event permit had only two requirements, both size-related. One allowed for events of fewer than 1,000 participants and the other for more than 1,000.

In a public meeting with the commissioners and the public works department, rancher Nancy Mucklow had a couple of ideas Tim Corrigan, a rancher, cyclist, backcountry skier and county commissioner, agreed with.

“One was to think about the process more like a land use process rather than a special event process,” said Corrigan, whose commissioner district takes in most of the southern half of Routt County and about a third of the county’s 25,000 residents.

Key in this arrangement for Mucklow and many other ranchers is the tie back to the 2022 Routt County Master Plan. Reflective of the desires of the community, it calls itself “an advisory document used by the county government to guide land development decisions.” Essential to it in many people’s minds is the importance it puts on the county maintaining its “rural character” while accommodating appropriate growth. For Mucklow’s husband, CJ, and many other ranchers, maintaining rural character translates to “keeping ag as part of the rural economy.” And for Nancy Mucklow, the only way to do that is “for the commissioners to be brave and visionary enough to block out some of these things that aren’t going to be good for us long term.”

In this situation “some of these things” includes SBT GRVL, which CJ Mucklow calls “ill-timed, ill-prepared and full of people racing who don’t care about trash or needing to go to the restroom. The liabilities are incredible. Fifteen hundred bikers looped our road for hours. One thousand, one hundred families live along County Road 129. And we are already the recreation area, with bikers, campers and snowmobilers, all year. For those visitors we put up the warm welcome. Then this came along and we knew about it but not the magnitude of it.”

In response to trash on the course, Amy Charity, SBT GRVL founder and owner, said, “Some of the stories (at the commissioners meeting) got embellished. And it was really rough, because we didn’t have a conversation.”

She created the opportunity for one on Nov. 9 by holding a listening session in the town of Oak Creek, 20 miles south of Steamboat on the southernmost end of the route. At that meeting, “someone raised their hand and said, ‘There’s trash everywhere, and it’s still there.’ We’d say, ‘Really?’ And we’d go out (to get it). It turned out there was a sign down and no one saw it, so we picked it up. But I was expecting Coke cans and Gu wrappers.”

As for people defecating on ranchers’ land, she conceded there weren’t enough port-a-potties and some riders were uneducated, but she’ll have more facilities this year and make it clearer that riders must respect private property.

At the commissioners meeting, Nancy Mucklow insisted the race had bigger issues, however. “We’re trying to get people to understand this is a race with a purse of many thousands of dollars,” she said. “People on bikes are exceeding the speed limit. It’s not safe.”

But there are plenty of people outside the Yampa Valley ranching community who think SBT GRVL is great.

SBT GRVL started five years or so after gravel biking emerged in Colorado, says Juan DelaRoca, publisher and editor of “Gravel Adventure Field Guide.” One of the first events was the Pony Xpress Gravel 160 in Trinidad in 2014, which came courtesy of long-time Leadville 100 competitor Phil Schweitzer who began scouting Las Animas County roads a couple years prior. Lifetime Fitness showed up in Trinidad in 2020 with The Rad Dirt Fest.

“But the post-pandemic era is, in general, when the gravel race event boom really accelerated,” said DelaRoca, “Now, just about every major mountain and Front Range town hosts an event or race series, with even newer ones popping up in off-the-radar gravel events like the West End Gravel Rush in Nucla, in the West End of Montrose County.”

Charity conceived of her race in 2018. Just off the bike racing circuit, she had a fat Rolodex of industry contacts. Between her network and “living in this incredible town of Steamboat,” where, among other things, she has chaired the chamber of commerce’s marketing committee for the past six years, she and her business partner, the former CEO of Smartwool, were in the right place at the right time to launch the event. Every year since, it has started and ended in downtown Steamboat Springs, while the courses have had “very, very small changes, like one road here, one road there,” she said.

She said she’s had little negative feedback from the community, except for in 2022, when some residents started saying “there’s some congestion on the road,” she added. The county responded by asking her to put signs on course during the race to alert the locals it was happening, which she did.

“We went big with those. We made huge signs,” she said. “We took that feedback and put those out so no one would be surprised. We put a banner across Lincoln Street, which is our main thoroughfare going either direction in Steamboat, and we went on Steamboat Radio during race week.”

Charity insists the ride transcends just pedaling through pastoral countryside or racing for a $22,000 prize purse. Over the past four years, organizers have donated $100,000 to area nonprofits, she says. They’ve partnered with the local Boys and Girls Club — teaching kids how to set goals and “have grit,” along with bringing them into bike culture through working at aid stations during the race.

They’ve taught Zoom spin classes for The Cycle Effect, preparing the largely Latino group of girls for the race. They’ve donated money to the Community Agriculture Alliance, a nonprofit preserving agriculture in the Yampa Valley. They support local search and rescue teams and the local United Way. And, since the race’s inception, they’ve welcomed the nonprofits Ride for Racial Justice and All Bodies on Bikes into the organization, creating opportunities for communities traditionally underserved in bike racing. Plus, every year around 7,000 race-related visitors flock to Steamboat Springs, generating “millions of dollars in our community,” Charity said.

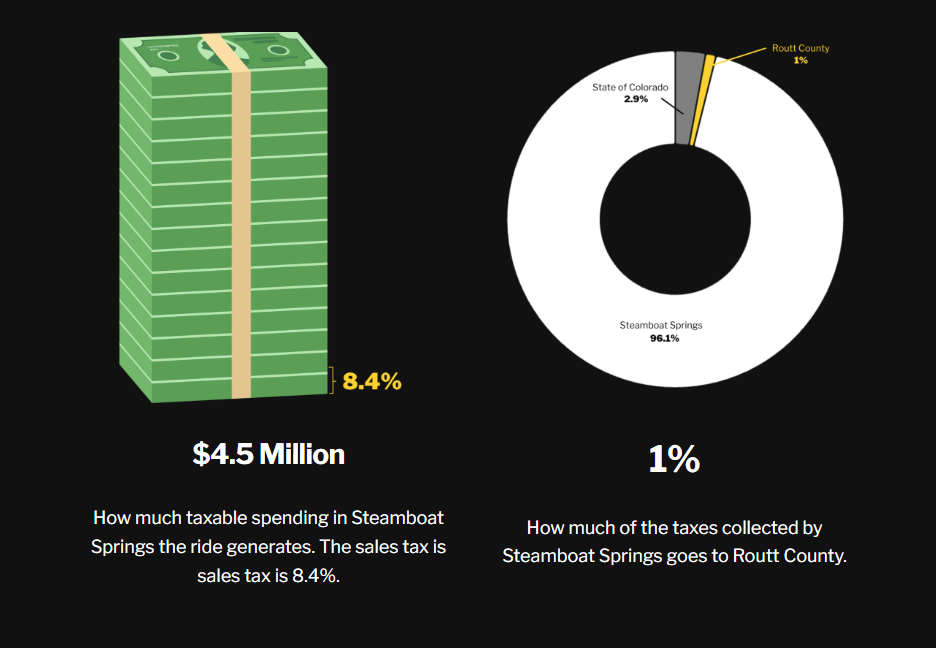

Mention this to naysayers and they’ll tell you the money stays within Steamboat’s city limits, which Corrigan, the county commissioner, confirms.

“Routt County has very restrictive zoning regulations that mostly prohibit commercial activity as well as an outright prohibition of short-term rentals in unincorporated Routt County,” he wrote in an email. “So, practically speaking, there aren’t any stores (except the small store in Clark), lodging facilities or any other operation that could benefit from any of this activity or any sales tax collections for the county.”

That means “virtually all of the economic benefit accrues to businesses and city of Steamboat sales tax revenues,” he added. “Short of some kind of direct payment to the affected residents it’s hard to see what kind of positive impact there could be.”

In an email, Charity said in 2023, the ride generated $4.5 million in taxable spending in Steamboat Springs, where sales tax is 8.4%. Of that tax revenue, 2.9% goes to the state of Colorado, 1% to Routt County and the remainder to the city. “Additionally, SBT GRVL has made a financial contribution to the Community Agriculture Alliance since its inception (more than $12,000),” she wrote.

And the race “is changing the face of cycling,” she said.

“You’ll have people who barely finish our 37-mile race, walking their bikes to the finish. Two years ago, we launched a (paraplegic) category, and now we work with 50 para athletes. The impact has been so large, the head of marketing at Steamboat resort, Morgan Bast, asked me, ‘How do you change the landscape of skiing like you’ve done in cycling?’”

With a second SBT GRVL race in Finland and a third on tap for South Australia, Charity’s focus on inclusivity could be far-reaching.

“So what would I say about us impacting the roads in our county and downtown Steamboat? I’d say we do. But the benefit to our town and the greater good far outweighs the impact on a public road that happens for a few hours on a Sunday.”

The ranchers at the October commissioners meeting insisted SBT GRVL lasts more than a few hours, and a quick look at the 2023 playbook confirms it.

Events started Aug. 17, with a “shakeout ride” four days before the race. It covered parts of the course, as did multiple rides on Friday. On Saturday, another ride looped around Steamboat, and on Sunday, the first race group left Steamboat at 6:30 a.m. with a cutoff time for the last rider to return at 8 p.m.

The four days comprising Charity’s event is just the “crescendo” of gravel biking in Routt County every year, says Tom Grimaldi, who has ridden the race annually since its inception and whose family has been ranching around Steamboat Springs since moving there from Kansas during the Dust Bowl years.

What happens now, thanks to the race’s global reach, magazines like Outside bringing it to millions of subscribers and the Office of Economic Development and International Trade’s push since 2020 to help rural towns develop and market their gravel biking offerings, “is a continuous influx of people” descending on Routt County to ride the undulating roads ribboning through it, Grimaldi said.

“On any given day events can be happening,” he added. Moots, a high-end maker of titanium bikes in Steamboat Springs, does them. Others flock there for vacation or gravel camps. “Ranchers have learned that race day is probably not the best day to move cattle. And this is the part that’s hard for people to understand. We’re out acting like a bunch of kids riding our bikes, and the ranchers are working. So with someone who doesn’t have a passion for the sport, take even the smallest of situations and it can get a little bit exacerbated.”

Marcus Robinson, founder of Ride for Racial Justice, wants the ranching community to know something, however. His organization partners with SBT GRVL, which provides free race entry to 30 of their riders. “For a BIPOC-led organization, that’s monumental,” he said.

“These are people who have never even experienced the mountains, who have never been in an open space, who have never been outside of a major city,” Robinson said. “So to give them a chance to ride a bike on a road with no cars or trucks, to sit down and look at a stream, or to watch a cow, that’s a life-changing experience. And it’s all because of Amy and her team. We, meaning them and us, are pushing the envelope to what true inclusion is supposed to look like in sport. No one is achieving what we’re achieving. I can’t even remember all the advocacy programs the race supports.”

But do the benefits to affinity groups or the riders who do SBT GRVL year after year outweigh impacts ranchers say include “intrusion into rural life,” “public defecation and urination,” “pack riding” and “hospitality of rural residents being taken advantage of”?

Grimaldi, the grandson of ranchers, doesn’t think so. But lifelong Routt County rancher Jay Fetcher says despite those dings, the race can bridge the worlds of ranching and recreation.

Fetcher’s dad and uncle founded Fetcher Ranch — on 1,400 acres near the town of Clark — in 1949 and his dad was a co-founder of Steamboat ski resort. Fetcher grew up ranching and was instrumental in the creation of the Colorado Cattlemen’s Agricultural Land Trust and a finalist for the 2021 Colorado Leopold Conservation Award. He said three years ago, Charity and Van Dyke came to him asking if they could route the longest loop of the race off County Road 129 through his property.

Agreeing to the proposition, Fetcher welcomed a handful of riders affiliated with SBT GRLV onto his land to do trail work through his 700-acre cow pasture.

Fetcher is careful to point out his property “is admittedly a little off the main road, so we didn’t quite have the impact of some of my neighbors” and that he “totally understand(s) and sympathize(s) with some of the issues they faced and went through in dealing with the bikers.”

But the plus for him was that Charity’s team put an aid station at the ranch, “so the bikers could stop and chat and talk and look around. That gave me and my family a chance to really share what we do here and talk about why we’re here and why this land is open, because of hay and cows and family.”

With four routes total and only two that went through the ranch, Fetcher said more mellow riders, “not the ones charging to the front of the line” stopped to visit. And he agrees with some of his neighbors that traffic on County Road 56, where many of the complaints originated, was bad. But Charity and Van Dyke “can work on that issue and it will help,” he said.

“We are losing ranches left and right,” Grimaldi said. “Some of the hay here is considered the best in the world. The importance of the agrarian part of Steamboat is immense and ranchers should do a better job of marketing themselves.”

“Recreation and agriculture are the backbones of Routt County,” Charity said. “We need each other to survive.”

If the commissioners decide to elevate SBT GRVL to a large special event status, its permitting will require an annual public hearing.

That could always turn out like the Oct. 16 meeting, but Corrigan said “the likelihood of the race simply not getting any kind of permit is pretty close to zero. The question is what is going to be the size of that permit and what are the conditions they’re going to have to comply with in order to get that permit. As I’ve explained to some people, we cannot arbitrarily discriminate against any particular event just because people don’t like it.”

She has eliminated two-way bike traffic on all courses and will use more rural roads to reduce traffic and resident conflicts. She’ll hire more safety marshals, police and state patrol for race day. She promises listening and information sessions for the rural community and a page dedicated to the same on the SBT GRVL website. And perhaps most important, she’s making registered riders sign an oath prior to the race that commits them to following the rules. If they break one they will be disqualified. Anyone can turn in an offending rider. The contact number will be available to the public, and riders will wear enlarged number plates for easy identification.

The 2024 race sold out a day after Charity learned the commissioners would be reexamining their permitting rules, but she said she’s never had a permit in hand before June, so likely this year is no different.

Corrigan said the county is almost finished with a draft of its new Special Event Permit process. Commissioners will be discussing that draft in a work session Jan. 22, and “will be entertaining public comment at both meetings,” he said. But DelaRoca, the field guide publisher, said there might be a bigger issue at hand.

He believes sometime in the near future gravel biking’s popularity may actually kill gravel biking in Colorado.

“Gravel events in general are great for towns looking to attract visitors, but I don’t think their trajectory is necessarily sustainable,” he wrote in an email. “Between May and September, every weekend hosts an event somewhere in and outside of Colorado. People are willing to travel 8+ hours in a car to spend money beyond race registration. Event fatigue is going to set in at some point.”

If or when that happens, he expects a number of events are going to fold, or sell to larger events as corporate dollars increasingly flow into the sport.

“If gravel is not thoughtful in its future development, then we’ll see the same thing happen to it that has befallen the road and mountain biking,” he added. “People will find themselves over it because it feels too overhyped and expensive.”

Article by Tracy Ross, Rural Reporter of the Colorado Sun.

Cycling Season is here, and so is a long list of epic rides throughout the state and surrounding states. Are you ready? Join Avid Cyclist, and other co-hosts for the

By: Brad Tucker I have been practicing law for over thirty-five years, the majority of which has included representing bicyclists who have been hit by drivers who disregarded the safety

April 8, 2025 Propelled by the powerful stories of victim families, SB25-281 includes new mandatory chemical testing clause BOULDER, CO /ENDURANCE SPORTSWIRE/ – The White Line, founded in memory of 17-year-old

Boulder, Colorado- After a week long trial, late Friday evening, a Boulder County jury found Yeva Smilianska guilty of Vehicular Homicide-Reckless Driving in the death of Magnus White. The jury,

The 2025 Karen Hornbostel Memorial Time Trial Series p/b Cobras Cycling Team has entered its second week! Ryan Muncy of Ryan Muncy Photography was there to capture images of a chilly afternoon. Make

By: Gary Robinson, Avid Cyclist Jury selection began Monday morning for the suspect driver accused of striking and killing Colorado teen cyclist Magnus White near his home in Boulder. Yeva