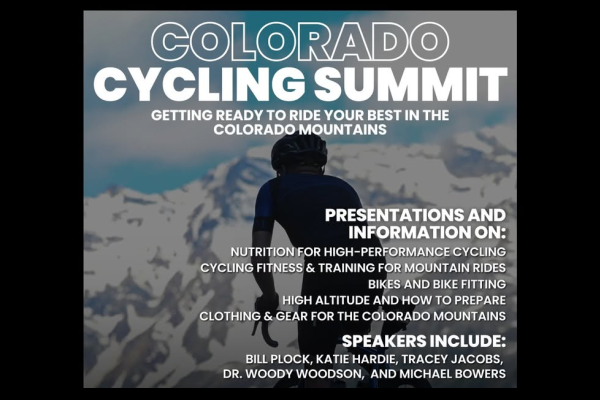

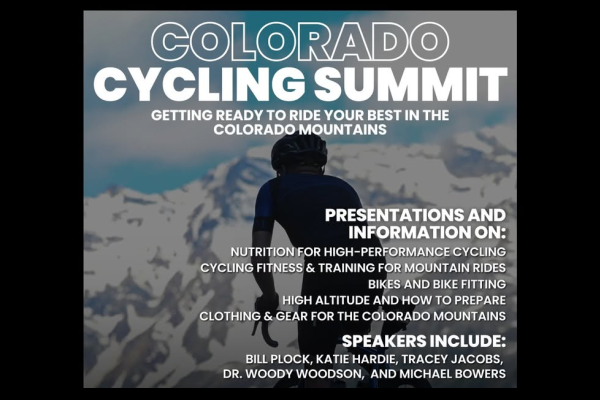

The First Colorado Cycling Summit

Cycling Season is here, and so is a long list of epic rides throughout the state and surrounding states. Are you ready? Join Avid Cyclist, and other co-hosts for the

CONIFER — A titanic battle of Colorado values and priorities is brewing over a proposed mountain bike park on a 9,000-foot mountain overlooking this quiet foothills community 40 minutes from Denver.

On one side are the thousands of cyclists who take to the state’s roads and trails every day, seeking the thrill and challenge of rolling across world-class terrain amid jaw-dropping settings. On the other are long-time mountain residents, adamant about keeping Colorado’s relentless growth at bay while protecting a peacefulness and quietude that is increasingly under strain.

The battle lines in this faceoff are drawn on a heavily wooded 250-acre parcel along Shadow Mountain Drive just west of Conifer, where a plan to build Colorado’s first dedicated lift-access mountain bike park — with 16 miles of trails and an 830-foot vertical drop spanned by a chairlift — has resulted in dueling campaigns for and against it.

A Change.org petition in support of the project has gathered nearly 2,500 signatures while an effort to stymie the plan has garnered around 4,400 signatures.

John Lewis, a member of a well-organized group fighting the proposed project, said he and his neighbors are ready for the Full Send Bike Ranch proposal to land in front of the Jefferson County Planning Commission. The men behind the project say that could come as early as next month, with a hoped-for opening in 2023 should the county give its blessing.

Lewis last week pointed to a vast slope of evergreen trees fronted by North Turkey Creek burbling through a sun-dappled mountain meadow as natural features he doesn’t want to see degraded or disturbed by the construction of a downhill mountain bike facility with a 300-space parking lot.

He worries about hundreds of vehicles traversing narrow Shadow Mountain Drive every day, negotiating blind curves and racing past driveways to reach the bike park. He worries about impacts to wildlife and to the bucolic views he and his neighbors have enjoyed for decades.

He also worries about an increase in wildfire danger — a flicked cigarette from a moving car, perhaps — to an area that is already tinder dry.

“It’s just not appropriate for a residential area,” Lewis said, driving his truck several miles up Shadow Mountain Drive and passing dozens of signs denouncing the project. “I don’t mind these guys building their bike park — but why here?”

“These guys” are Jason Evans and Phil Bouchard, lifelong friends and bike aficionados from New Hampshire who moved to Colorado last year just as the COVID-19 pandemic was descending on the state. Bouchard, who describes himself as the “strategy” side of the Full Send operation, defends the project as a net gain for the Conifer area.

He said he and his business partner will be working with the U.S. Forest Service to do major wildfire mitigation on the site, removing dead and down trees to make it far safer than it is now. And he said the Full Send Bike Ranch will help draw cyclists off other trails in the area that are currently overcrowded.

“We think the park will alleviate a bit of pressure on a lot of trail systems,” Bouchard said.

Opponents, he said, have painted the project as an assault to the neighborhood. But there will be no nighttime operations lit up with bright lights and no plans to have competitions with loudspeakers blaring riders’ names and results, Bouchard said.

“It’s a relatively low-impact recreational development that is closed six months of the year,” he said.

The park, he said, answers an unmet demand from Colorado’s avid cycling community. While a number of the state’s ski resorts — including Breckenridge, Keystone and the popular Trestle at Winter Park — offer lift-assisted downhill freeride mountain bike runs, Bouchard said they are sideshows to their primary ski operations.

“It’s just about the riding,” he said of Full Send Bike Ranch.

Full Send would be just over a half hour from the metro area via U.S. 285, and because it’s at a lower elevation than the state’s ski resorts, could be open for more days in the year — with a season extending from April to November.

“If you want to go mountain biking, you don’t have to wait until Saturday and put in a three-hour commute on Interstate 70,” Bouchard said. “You could go after work on a Wednesday.”

Plans also call for a lodge where riders can enjoy a beer after a run. Tickets would be priced at $50 to $80 a day, with season passes available, Bouchard said. The effort to build the park would be a multi-million dollar one, money Bouchard and his partner are confident they can raise if the project is approved by Jefferson County.

The friends are working on a lease arrangement with Colorado’s State Land Board, which owns the parcel.

Gary Moore, executive director of the Colorado Mountain Bike Association, said the Full Send Bike Ranch “scratches an itch” among the state’s earnest pedalers.

“They’re coming at this from a clean sheet design,” he said. “They could really just do what they want to do without facing restraints. There’s a huge contingent of mountain bikers on the Front Range that aren’t getting access to that style of riding.”

But neighbors point to Jefferson County’s own Conifer/285 Area Plan, updated in 2014, which notes that residents “value the community’s natural environment and rural neighborhoods.”

“Passive and active recreation facilities, including recreational buildings and outdoor multi-use fields, should be designed to respect and be compatible with the area’s natural resources, rural character and adjacent land uses,” the document states.

That’s where the proposed facility falls woefully short, said Todd Jeffries, who serves on the safety committee for the Stop Full Send Bike Ranch group. Cutting trails through the forest and building a large parking lot near to where North Turkey Creek flows through will have long-lasting negative impacts on the wildlife that call the area home.

And what if the project doesn’t pencil out in the long term?

“(The land) could never be brought back to the condition it was in,” Jeffries said. “This place will be permanently scarred.”

John Patrick, who lives on 10 acres across Shadow Mountain Drive from the proposed bike park, said its mere presence would be enough to drive him from his neighborhood of 38 years.

“This is God’s country,” he said, gazing across a meadow to the mountains beyond. “We got mountain lions, we got elk, we got bears, we’ve even had moose. I never thought I’d have to leave — but I’d be moving.”

Cycling Season is here, and so is a long list of epic rides throughout the state and surrounding states. Are you ready? Join Avid Cyclist, and other co-hosts for the

By: Brad Tucker I have been practicing law for over thirty-five years, the majority of which has included representing bicyclists who have been hit by drivers who disregarded the safety

April 8, 2025 Propelled by the powerful stories of victim families, SB25-281 includes new mandatory chemical testing clause BOULDER, CO /ENDURANCE SPORTSWIRE/ – The White Line, founded in memory of 17-year-old

Boulder, Colorado- After a week long trial, late Friday evening, a Boulder County jury found Yeva Smilianska guilty of Vehicular Homicide-Reckless Driving in the death of Magnus White. The jury,

The 2025 Karen Hornbostel Memorial Time Trial Series p/b Cobras Cycling Team has entered its second week! Ryan Muncy of Ryan Muncy Photography was there to capture images of a chilly afternoon. Make

By: Gary Robinson, Avid Cyclist Jury selection began Monday morning for the suspect driver accused of striking and killing Colorado teen cyclist Magnus White near his home in Boulder. Yeva